The ‘metaverse’ has undoubtedly become one of the most successful Web3 buzzwords to seep its way into mainstream consciousness.

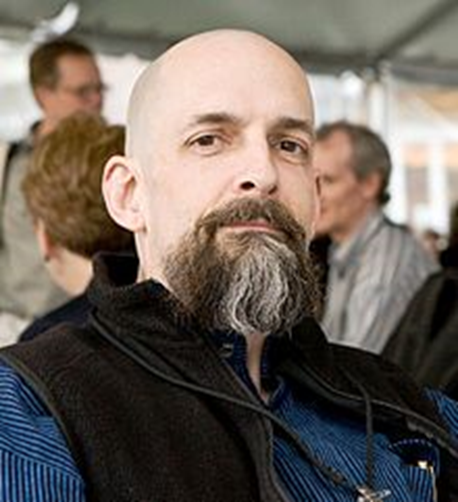

The term was first coined by American writer Neal Stephenson, in his 1992 novel ‘Snow Crash’. Thirty years on- and thanks to blockchain technology- the seemingly futuristic concept has now become somewhat of a reality for modern consumers.

However, for now, its definition remains bipartite in nature, as first and foremost, Stephenson’s definition revolves around the metaverse being the sole, perfectly interoperable, and all-encompassing digital realm for human existence.

Of course, such reality remains long in the future for now, meaning by virtue, the ‘metaverse’ platforms of today take-on a different definition- i.e., one that’s narrower, more stringent, and bound by many technological, social, and adoption-centric parameters.

Modern Day Metaverse Platforms

When it comes to the ‘modern’ definition of the metaverse, this relates to the tangible examples that we see today- i.e. examples that despite not replicating Stephenson’s grand vision just yet, still do a fine job in showcasing what the ‘end game’ metaverse may look like, as well as Stephenson’s weight as a somewhat ‘visionary’ figure.

When it comes to the modern definition of the metaverse, there are a handful of projects that lead the way when it comes to showcasing what decentralised living can entail- these include the likes of Decentraland (DCL), The Sandbox, and Spatial.

The key words here- i.e., something that distinguishes the ‘end game’ definition from its ‘modern’ counterpart- is ‘interoperability,’ as whilst many of today’s metaverse platforms offer a host of interoperable features, making them perfectly interoperable with one another is an arduous task to say the least.

What this is essentially means for users is that each platform has its own fundamental focus and tokenomics system to render it unique. Here, for example, in the case of the voxelised world of The Sandbox, it’s all about using NFT assets to create gaming and social experiences for other users to enjoy (which, to be clear, is a very brief explanation). On the flip side, DCL adopts a more traditional animated aesthetic, whilst offering users to the opportunity to engage in many ‘life-like’ events and other interactive experiences.

What this essentially means is that through today’s technological and creative limitations, The Sandbox can’t (and doesn’t) do what DCL does (and vice versa), nor are the pair interoperable with one another.

Another key element of today’s metaverse platforms is blockchain tech- i.e. what’s leveraged in order for players to truly own their metaverse avatars, land, wearables, and accessories etc. With each platform being built on a particular blockchain, assets in which users own on one platform may be completely obsolete on another, which again, is a problem of based around perfect interoperability (or the lack thereof).

Thankfully, on this front, there is currently a ton of developments in blockchain bridges (a.k.a cross-bridges), which in turn, will be pivotal in laying the foundations for Stephenson’s ‘end game’ metaverse reality.

A final talking point surrounding today’s lack of full interoperability comes by way of graphics, as previously alluded to, platforms adopt different rendering aesthetics, which in turn, make it hard for them to become interoperable with one another.

Whilst such issue will quite likely remain prevalent for some time, some Web3 developers are already looking to solve it. For example, industry-leading 3D metaverse avatar creator Ready Player Me has launched an avatar API that allows users to transport/use their avatars across multiple different platforms.

The Expansion of The Definition

Whilst for many these forms of blockchain-built decentralised worlds serve as our purest manifestations of the metaverse (thus far), the term is also often referenced- wrongly or rightly- when any of its particular characteristics are involved in a project.

For example, through the involvement of blockchain technology, NFT and other Web3 projects often dub their ecosystems as ‘metaverses’ (i.e. purchase an NFT to join the ‘X’ metaverse), despite the only metaverse-esque element being blockchain technology and decentralised ownership.

On the flip side, the term is also sometimes used when a platform’s user experience mimics that of metaverse living, despite their being the omission of blockchain elements. Without a doubt, the best example of this is Roblox, which is a widely popular online game and team creation platform that allows users to program their own in-game experiences for others to enjoy. With over 67 million active users, and around 214 million monthly active users (per Demand Sage), the game is dubbed as today’s biggest ‘metaverse,’ despite not featuring any blockchain elements.

Final Thoughts

Whilst the technological and adoption-related limitations of today render Stephenson’s metaverse ‘end game’ nothing but a thing of the distant future, it’s safe to say that the metaverse ‘ball’ is certainly up and running.

In conclusion, we can view today’s metaverse climate as one which exhibits ‘end-game elements in isolated pockets,’ as through blockchain-based ownership and DAO governance systems, we are certainly heading in the right direction.

That being said, a pivotal word here is ‘elements,’ as by no means do any of today’s platforms allow users to enjoy perfectly immersive and effectively life-like experiences on a 24/7 basis- nor anything close to that.